The Hamitic Hypothesis – Rethinking Melchizedek’s Lineage

“And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God.” – Genesis 14:18 (KJV)

Reexamining an Ancient Mystery

Having surveyed the traditional identification of Melchizedek with Shem and seen its theological elegance yet geographical inconsistency, we now turn to the alternative view—the Hamitic Hypothesis. This interpretation begins where the text itself begins: with the land, the lineage, and the divine order of blessing.

In Genesis 14:18–20, Melchizedek appears suddenly, blessing Abram and receiving tithes as priest of El Elyon, “the Most High God.” He rules in Salem, later called Jerusalem, a city located deep within the inheritance of Canaan, the son of Ham. He blesses Abram in the name of the same God Abram worships, recognizing the universal sovereignty of the Creator.

Every clue embedded in the narrative points toward a human priest-king who ruled within the borders of Ham’s inheritance and carried the priesthood established after the flood. When the evidence is examined in full, the conclusion emerges naturally: Melchizedek was Ham, the son of Noah.

The Land of Canaan: Ham’s Inheritance

The strength of this thesis lies first in geography. Genesis chapter 10—the Table of Nations—records that the descendants of Ham settled in Africa and Canaan, while Shem’s line occupied lands east of the Euphrates:

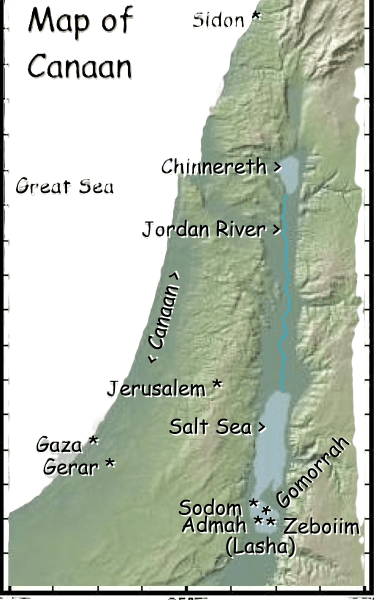

“And the sons of Ham; Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan… And the border of the Canaanites was from Sidon, as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza; as thou goest, unto Sodom, and Gomorrah, and Admah, and Zeboim, even unto Lasha.”

— Genesis 10:6, 19 (KJV)

The city of Salem, later identified as Jerusalem, stood squarely within this boundary. Its earliest inhabitants were the Jebusites, who were descendants of Canaan (Genesis 10:15–16). Thus, Salem was a Canaanite city, and its ruler would naturally have been a son of Ham’s lineage.

If Scripture is to be taken literally, the conclusion is unavoidable: the king of Salem was a Hamite. It would be theologically improper—and geographically contradictory—to place Shem as ruler over a land divinely allotted to Ham. To do so would overturn the very divisions of the nations decreed by the Most High (Deuteronomy 32:8–9).

Melchizedek as Patriarchal Priest

After the flood, priesthood was patriarchal. Noah, as father of all mankind, served as the first postdiluvian priest, offering sacrifices and pronouncing blessings. His three sons—Shem, Ham, and Japheth—each inherited not only lands but spiritual oversight over their respective nations.

Each was a priest-king in his own domain:

| Son of Noah | Domain | Function |

| Shem | Mesopotamia and Aram | Covenant line through Abraham |

| Ham | Canaan, Egypt, and Cush | Priestly king over Hamitic nations |

| Japheth | Northern regions | Expansion of nations and trade |

Thus, the priesthood of Melchizedek was not a novelty but the continuation of Noah’s priestly order, distributed among his sons. If Melchizedek ministered in Canaan, he did so as the patriarchal priest of Ham’s house, not as a foreign ruler.

Blessing Before the Covenant

One of the most decisive evidences for Ham’s identification as Melchizedek is the order of blessing in Scripture. The writer of Hebrews builds his argument on this principle:

“And without all contradiction the less is blessed of the better.”— Hebrews 7:7 (KJV)

In Genesis, blessing descends from the greater to the lesser—from God to man, from patriarch to descendant, from elder to younger. Only those blessed directly by God could stand above Abraham and bless him in return.

The record of divine blessing is unmistakable:

| Blessed Figure | Scripture | Nature of Blessing |

| Noah and his sons | Genesis 9:1 | “God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” |

| Abram | Genesis 12:2 | “I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing.” |

Only Noah and his sons were blessed before Abraham. Therefore, only one of them could be “greater” than Abraham in spiritual authority. Since Melchizedek blesses Abraham and receives tithes from him, he must be one of these original blessed patriarchs.

Among them, only Ham fits the geographic and narrative context. The priest-king of Salem, ruling in Canaan, blessed Abraham on ground that had been his inheritance from God since the division of the nations.

The Logic of Divine Consistency

If Melchizedek was Ham, this identification does not conflict with God’s holiness—it magnifies His mercy. For while Noah pronounced a curse upon Canaan (Genesis 9:25), Ham himself was never cursed. The Scripture is clear:

“And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” — Genesis 9:1 (KJV)

No human tongue could revoke what God had blessed. Even Balaam, centuries later, declared, “Behold, I have received commandment to bless: and he hath blessed; and I cannot reverse it.” (Numbers 23:20).

Thus, Ham remained a blessed patriarch, though his son Canaan would bear the weight of servitude. The curse upon Canaan’s descendants did not diminish Ham’s own standing before God. If anything, the transformation of that curse into sacred service—as the Gibeonites and Nethinim later became servants in the temple—reveals the depth of divine redemption at work through Ham’s line.

A Universalist Priesthood

If the priesthood of Shem prefigured the covenantal priesthood of Israel, then the priesthood of Ham prefigured the universal priesthood of the nations. Melchizedek’s office represented not a national covenant but a human one—priesthood as it existed before ethnic boundaries and before law.

By blessing Abraham, Ham symbolically joined the two priestly streams of humanity:

- The universal priesthood of creation (through Ham).

- The covenantal priesthood of redemption (through Shem).

The bread and wine offered by Melchizedek thus become the first recorded sacramental act of fellowship between these two orders. They foreshadow the Seudat HaBrit—the covenant meal—that Messiah would later institute, joining Jew and Gentile, Shemite and Hamite, into one redemptive body under the Most High God.

The Silence of Scripture: Without Genealogy

Hebrews 7:3 describes Melchizedek as “without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life.”

This does not mean Melchizedek was immortal or divine. It means that Scripture records neither his ancestry nor his death—his priesthood exists in the text without genealogical interruption.

“For this Melchizedek… first being by interpretation King of Righteousness, and after that also King of Salem, which is King of Peace; without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life; but made like unto the Son of God; abideth a priest continually.”— Hebrews 7:1–3 (KJV)

Shem’s lineage and death are recorded (Genesis 11:10–11). Japheth’s lineage is preserved in the Table of Nations. But Ham’s genealogy ends abruptly, and Scripture never mentions his death. This silence matches precisely the description in Hebrews: a priest whose origin and end are unrecorded.

Thus, Ham’s literary absence in the latter part of Genesis is not neglect—it is typology. His silence becomes the very mark of Melchizedek’s priesthood: continuous, unbroken, and without record.

Theological Implications: Grace in Reversal

The Hamitic Hypothesis overturns centuries of inherited stigma. It restores Ham not as the father of a curse, but as the vessel of grace. It shows that divine priesthood is not confined to one race, line, or covenant, but arises wherever God appoints righteousness.

Ham’s identification as Melchizedek reveals a stunning truth: the first priest of the Most High after the flood emerged from the line accused of shame. The servant became a priest; the marginalized, a minister; the forgotten, a figure of eternal righteousness.

In this reversal we see the pattern of divine redemption—a pattern fulfilled in the Messiah, who likewise “made himself of no reputation” (Philippians 2:7), yet became the eternal High Priest “after the order of Melchizedek.”

Conclusion: The Priest of Canaan, The God of All

Melchizedek’s priesthood in Salem was no accident of history. It was the unfolding of a divine plan written into the earliest pages of Scripture. The priest-king who blessed Abraham was not a stranger from Shem’s line, but the patriarchal elder from Ham’s—one who ministered faithfully within the inheritance God had given him.

The Hamitic Hypothesis resolves the geographical paradox, upholds the divine order of blessing, and restores to Ham his rightful dignity as a servant of the Most High.

In the next installment, we will explore how this reinterpretation transforms our understanding of the so-called “Curse of Ham,” demonstrating that the true offender was Canaan, not Ham, and that the curse itself was providentially turned into sacred service within the house of God.

“The Lord reigneth; let the earth rejoice; let the multitude of isles be glad thereof.”

— Psalm 97:1 (KJV)

Your voice matters. Iron sharpens iron. What insights or questions do you bring to the table?