The Traditional View – Shem as Melchizedek

“Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.” – Genesis 9:26 (KJV)

The Birth of a Tradition

For centuries, Jewish and Christian interpreters alike have identified Melchizedek with Shem, the son of Noah. From the Targums to the writings of early church fathers such as Ephrem the Syrian and Jerome, this tradition became so deeply rooted that few dared to question it. To many, it seemed only natural that the mysterious “priest of the most high God” who blessed Abraham must have been Shem, the patriarchal ancestor of Abraham’s own line.

The reasoning behind this interpretation was straightforward and, on the surface, deeply appealing. Shem was the “blessed” son of Noah, through whom the knowledge of the true God continued. Noah’s blessing upon Shem, “Blessed be the Lord God of Shem,” appeared to confer upon him a special relationship with the Almighty (Genesis 9:26). Thus, the rabbis reasoned that Shem must have been the custodian of divine worship in the post-flood world — the priest of the Most High, serving God long before the Law or the Levitical priesthood.

This interpretation was reinforced by the Jewish concern for maintaining the “righteous line” — an unbroken chain of faithful patriarchs linking Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem, and Abraham. It allowed the priesthood of Melchizedek to remain within the same spiritual bloodline that would later culminate in Israel’s covenant.

But as noble as the intent was, the tradition stands on foundations more theological than textual. The Bible never identifies Melchizedek as Shem. The connection rests entirely upon inference and pious continuity — and not upon the plain evidence of Scripture itself.

The Theological Appeal of the Shem Theory

The Shem identification answered several theological and genealogical concerns for early interpreters.

1. Continuity of Righteousness – The Genesis narrative traces a deliberate line of righteousness from Adam through Seth to Noah and then to Shem. It seemed natural that the priesthood of the Most High God would be preserved within this chosen lineage.

2. The “God of Shem” Connection – Noah’s prophetic blessing explicitly links YHVH with Shem:

“Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.” — Genesis 9:26 (KJV)

If the Lord is called “the God of Shem,” then Shem must be the one who worships Him rightly. Thus, the priest of the true God in Abraham’s time would, it was reasoned, be none other than Shem himself.

3. Righteous Predecessor to Abraham – Shem lived for six hundred years (Genesis 11:10–11), which means his lifespan extended well into the time of Abraham. In fact, by most biblical chronologies, Shem was still alive when Abraham was born and remained alive for more than thirty-five years of Abraham’s life. This made it plausible that Abraham could have met Shem personally.

4. Guarding the Unbroken Line of Monotheism – The Shem theory prevented any notion that Abraham might have learned the worship of God from an unrelated or non-Hebrew source. By identifying Melchizedek with Shem, interpreters ensured that monotheism passed neatly from father to son — from Noah to Shem, from Shem to Abraham, and from Abraham to Israel.

Thus, for ancient rabbis and theologians, Shem-as-Melchizedek served as both protector of theological order and symbol of continuity.

The Strength of the Shem Tradition

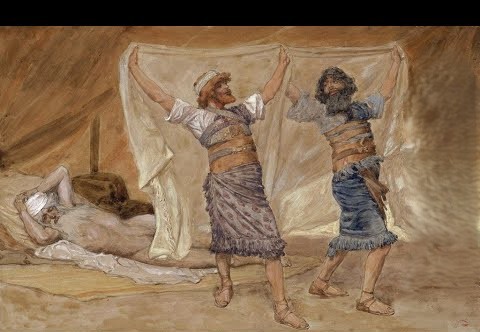

The Shem identification also carried a powerful moral appeal. Shem was the son who showed reverence for his father Noah, walking backward with Japheth to cover their father’s nakedness (Genesis 9:23). His act of modesty contrasted sharply with Ham’s perceived irreverence.

This moral distinction gave Shem a status of righteousness and spiritual integrity that made him the logical choice for priesthood. If the Levitical priesthood demanded holiness and reverence, surely the first postdiluvian priest-king would emerge from the son who exemplified those traits.

Furthermore, ancient interpreters found comfort in the idea that God’s priesthood could never fall into the hands of those considered “cursed.” Since Noah’s curse fell upon Canaan, Ham’s son, tradition assumed that any holy office must remain within Shem’s blessed line.

Therefore, to identify Melchizedek as Ham would have been unthinkable to rabbinic and early Christian writers — a violation of moral hierarchy, a disruption of divine order, and, to their minds, a theological impossibility.

The Geographical and Textual Problem

Yet, for all its elegance, the Shem theory collapses under the weight of Scripture’s own geography. According to the Table of Nations (Genesis 10), Shem’s descendants settled primarily in Mesopotamia — the lands east of the Euphrates River — while the land of Canaan, where Salem (Jerusalem) stood, was allotted to the descendants of Ham.

The boundaries are explicitly defined:

“And the border of the Canaanites was from Sidon, as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza; as thou goest, unto Sodom, and Gomorrah, and Admah, and Zeboim, even unto Lasha.” — Genesis 10:19 (KJV)

The city of Salem, later called Jerusalem, lay squarely within this region — within the inheritance of Canaan, son of Ham. If Melchizedek ruled as king of Salem, his throne stood in Hamitic territory, not Shemitic.

To place Shem in Canaan would be to uproot him from the inheritance God had appointed to him and install him as ruler in his brother’s domain — something that would contradict the divine division of nations declared in Deuteronomy 32:8. The very boundaries that defined the post-flood world refute the idea that Shem reigned as priest-king in Canaan.

Chronological Incongruities

While Shem’s long life overlaps with Abraham’s, Scripture never once mentions a meeting between them. In fact, Shem disappears from the narrative long before Abraham enters the stage. Genesis 14 introduces Melchizedek without reference to ancestry, as though his identity were shrouded deliberately.

Had Shem truly been Melchizedek, one would expect at least a hint of recognition between the two — an acknowledgment of kinship or a genealogical note linking them. Yet the text is silent. Abraham treats Melchizedek not as a relative, but as a mysterious superior — a priest and king greater than himself, deserving of tithes and honor.

“And without all contradiction the less is blessed of the better.” — Hebrews 7:7 (KJV)

If Melchizedek were Shem, Abraham would have been blessing his elder by birth, but not necessarily his superior in spiritual rank. The text, however, insists on Melchizedek’s superiority — not in age, but in divine appointment.

The Problem of Recorded Death

Another inconsistency arises in Hebrews 7:3, where Melchizedek is described as “without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life.”

This language does not mean Melchizedek was immortal or divine; it refers to the absence of recorded genealogy or death in Scripture. The Levitical priests were established through documented lineage, but Melchizedek’s priesthood existed outside that system — his record silent, his origin unstated, his death unrecorded.

However, Shem’s genealogy and death are recorded:

“These are the generations of Shem: Shem was an hundred years old, and begat Arphaxad two years after the flood: and Shem lived after he begat Arphaxad five hundred years, and begat sons and daughters.” — Genesis 11:10–11 (KJV)

This explicit record of Shem’s life and death directly contradicts the portrayal of Melchizedek as “without descent.” Therefore, Shem cannot fit the description given in Hebrews.

A Tradition of Theological Necessity

The identification of Melchizedek with Shem arose not from textual evidence but from theological necessity. The rabbis sought to safeguard the sanctity of Shem’s line as the sole vessel of divine revelation. In their eyes, Ham’s descendants, cursed through Canaan, could never produce a righteous priest.

Yet this assumption reveals as much about human prejudice as it does about divine purpose. The Shem theory was an attempt to contain God’s righteousness within one lineage — to keep holiness “in the family.” It satisfied human logic, but not divine sovereignty.

The God of Scripture, however, is not bound by the genealogies of men. He raises up servants from unexpected places. The same God who chose Cyrus the Persian to be His “anointed” (Isaiah 45:1) and the same Lord who raised Rahab and Ruth from Gentile nations into His covenant could likewise raise up a priest-king from the line of Ham.

Conclusion: The Tradition and Its Limits

The Shem identification is a venerable tradition, rich with reverence but poor in textual support. It maintained a neat theological symmetry, ensuring that righteousness flowed unbroken from Noah to Abraham. Yet Scripture’s geography, chronology, and narrative silence tell another story.

If the priest of Salem stood upon Canaanite soil, ruled over Canaanite descendants, and bore a priesthood unlinked to recorded genealogy, then he could not have been Shem. The text demands another explanation — one that honors both the divine order of nations and the integrity of Scripture.

In the next part of this series, we will turn from tradition to revelation — from the Shemitic assumption to the Hamitic alternative — and examine how the land, the language, and the logic of blessing reveal that Melchizedek was Ham, the patriarchal priest-king of Canaan, and the first righteous servant to prefigure the universal priesthood of peace.

“For the Lord is the great God, and a great King above all gods. In his hand are the deep places of the earth: the strength of the hills is his also.” — Psalm 95:3–4 (KJV)

Next in the Series:

The Hamitic Hypothesis – Rethinking Melchizedek’s Lineage

Your voice matters. Iron sharpens iron. What insights or questions do you bring to the table?