Dividing the Nations: The Inheritance of the Sons of Noah

“When the most High divided to the nations their inheritance, when he separated the sons of Adam, he set the bounds of the people according to the number of the children of Israel.” – Deuteronomy 32:8 (KJV)

The Divine Division of the Earth

After the flood, when the waters subsided and Noah’s family stepped upon a cleansed earth, humanity began anew. Three men — Shem, Ham, and Japheth — carried within them the seed of every nation that would ever arise. Yet the earth they inherited was not theirs to divide as they pleased; it was apportioned by the sovereign decree of El Elyon, the Most High God.

The book of Deuteronomy declares this with poetic precision:

“When the most High divided to the nations their inheritance, when he separated the sons of Adam, he set the bounds of the people according to the number of the children of Israel. For the Lord’s portion is his people; Jacob is the lot of his inheritance.” — Deuteronomy 32:8–9 (KJV)

These words look backward and forward at once — backward to the primeval division after the flood, and forward to the eventual establishment of Israel in its promised land. They reveal that the nations did not emerge by human conquest or chance, but by divine appointment. The God who numbers the stars also numbers the borders of men.

The Most High and His Council

The title Most High (Elyon) appears here in its first explicit covenantal sense. It portrays God as the supreme Sovereign who governs the destinies of nations. The ancient text preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Septuagint expands this picture even further:

“When the Most High divided to the nations their inheritance… He set the bounds of the people according to the number of the sons of God.”

In this rendering, the phrase “sons of God” (bene elohim) refers to the divine council — heavenly beings who administer the nations under the sovereignty of God. The Most High delegates oversight, yet keeps one nation as His personal possession: “For the Lord’s portion is his people; Jacob is the lot of his inheritance.”

The pattern is clear: the world was distributed under heaven’s authority, and the nations received both land and spiritual jurisdiction. Yet Israel belonged to God directly, with no mediator between them. This structure frames the rest of Scripture — and it also frames the mystery of Melchizedek.

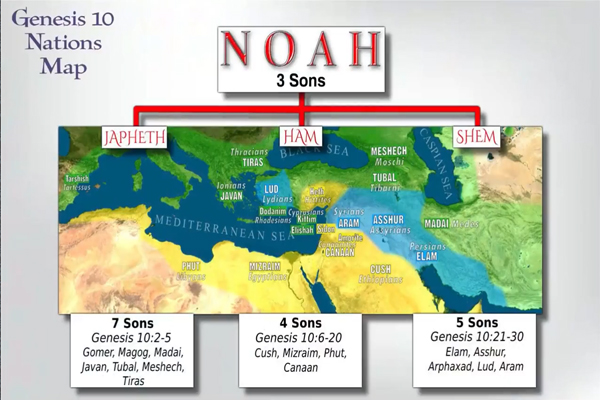

The Table of Nations: Humanity Reordered

Genesis chapter 10, the “Table of Nations,” records the outcome of that division. It is not merely a genealogy but a cartography — a map written in bloodlines. It tells us who settled where, and to whom each region was divinely assigned.

“Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and unto them were sons born after the flood.”— Genesis 10:1 (KJV)

From these three lines, the nations spread out “every one after his tongue, after their families, in their nations” (Genesis 10:5, 20, 31). The pattern repeats three times — once for each son — emphasizing that the division was complete and ordained.

Table: The Division of the Nations After the Flood

| Son of Noah | Primary Descendants | Geographic Domain |

| Shem | Elam, Asshur, Arphaxad, Lud, Aram | Mesopotamia, Assyria, Elam—lands east of the Euphrates |

| Ham | Cush, Mizraim, Phut, Canaan | Africa and Canaan—lands south and west of the Fertile Crescent |

| Japheth | Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, Tiras | Northern regions—Europe and Asia Minor |

This division is not arbitrary. It mirrors divine intention: three patriarchs, three spheres, three priestly jurisdictions. Each son became both ruler and priest over his allotted portion of humanity.

The Territorial Inheritance of Ham

Among these, Ham’s inheritance was the most fertile and strategically central. Genesis lists his four principal sons: “And the sons of Ham; Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan.” (Genesis 10:6, KJV).

From these four streams flowed the civilizations of early antiquity:

Cush settled in the upper Nile and the Horn of Africa.

Mizraim became the progenitor of Egypt.

Phut dwelt westward, along the coast of North Africa.

Canaan occupied the Levant — the land bridge between Africa and Asia, stretching from Sidon to Gaza, and from Sodom to Gerar.

The text concludes:

“And the border of the Canaanites was from Sidon, as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza; as thou goest, unto Sodom, and Gomorrah, and Admah, and Zeboim, even unto Lasha.” — Genesis 10:19 (KJV)

This description unmistakably situates the land of Canaan — and thus the city of Salem, later Jerusalem — within Ham’s territory. The entire region of Palestine was part of his divine inheritance.

Therefore, any ruler or priest who reigned in Salem in Abraham’s day did so upon Hamitic ground, not Shemitic. The city was Canaanite before it was Israelite, and its soil bore the mark of Ham’s dominion.

The Geographical Paradox of Shem as Melchizedek

This territorial fact creates a profound tension within the traditional rabbinic identification of Melchizedek as Shem. Shem’s descendants dwelt east of the Euphrates — in Ur of the Chaldees, Elam, and Assyria. Abraham himself was born among them, in the region of Ur, within Shem’s inheritance.

When Abraham journeyed westward into Canaan, he crossed out of Shem’s domain and entered Ham’s. There, he encountered Melchizedek — king of Salem, priest of the Most High God — who blessed him in the name of the same God he worshiped.

This raises a question that cannot be ignored: why would Shem, whose territory lay in Mesopotamia, be ruling as king in Canaan, the land allotted to his brother Ham?

The geography of Genesis leaves no room for Shem to claim dominion there. If Melchizedek reigned in Salem, he must have been of the lineage appointed to that land. The priest-king of Salem belonged, therefore, to Ham’s family line.

Theological Implications: God’s Order of Boundaries

The divine order of land and lineage is not merely historical — it is theological. God is a God of order. The allotment of the earth among Noah’s sons was not a random dispersion but a sacred geography that reflected divine wisdom.

“From one blood hath made all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation.” — Acts 17:26 (KJV)

The Apostle Paul, centuries later, affirmed this same truth. God not only created humanity from one source but also “determined” both their eras and their territories. To cross into another’s inheritance without divine sanction was to step outside the order of heaven.

If, therefore, Shem’s domain lay east of the Euphrates, and Ham’s lay westward in Canaan, then the king-priest who ruled in Salem under the title “priest of the Most High God” could not have been Shem. His very position as king in Canaan identifies him as belonging to the house of Ham.

From Division to Destiny

The division of the earth among Noah’s sons set the stage for all future history. Shem’s line would carry the covenant; Japheth’s would spread across the isles; Ham’s would dwell in the fertile lands of the south and west. Yet within Ham’s inheritance, God planted a seed of righteousness — a priesthood that would one day meet and bless the covenant bearer himself.

The meeting between Abraham and Melchizedek was not an accident of geography but the convergence of divine appointments: the covenantal line of Shem encountering the priestly line of Ham, both serving the same God under different aspects of His will.

Conclusion: A World Ordered by the Hand of God

The division of the nations was not a political act but a sacred ordinance. Every border, every tribe, every tongue was appointed by the Most High. The land of Canaan belonged to Ham by divine decree, long before Israel’s conquest.

To recognize this is to see that Melchizedek’s priesthood was not an anomaly but a manifestation of God’s universal sovereignty. The priest of Salem was not trespassing upon Shem’s inheritance; he was ministering within his own.

And thus, when Abraham met Melchizedek, he met not a stranger, but an elder — not a rival, but a patriarchal priest of the same God who would later reveal Himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

In the next part of this series, we will examine how tradition came to identify Melchizedek with Shem, and why this interpretation, though ancient, fails to reconcile with the geography, genealogy, and divine order that Scripture itself so carefully preserves.

“For the most High is terrible; he is a great King over all the earth. He shall choose our inheritance for us.” — Psalm 47:2, 4 (KJV)

Your voice matters. Iron sharpens iron. What insights or questions do you bring to the table?